I grew up in a coastal town in Maine, where there were many family farms. My brother and I sometimes worked on the weeding crews. We also spent a lot of time at our grandparents’ farm, learning and probably getting in the way, as they planted, weeded, and harvested from late spring to early fall. Some of my first memories are of helping my grandmother shell peas on the sun porch and of going down cellar carrying jars of canned vegetables. By the end of the summer glass mason jars filled with beans or corn or rhubarb, and sealed with red rubber rings, stretched along all the shelves.

Outside my grandfather would be picking and husking corn. And although he was getting too old to do the haying himself, he was always working on splitting wood for his wood pile.

Fast forward about 15 years and my husband and I were doing much the same things on a small farm of our own.

In the spring we planted vegetables and waded with buckets of food among little squealing piglets.

In the spring we planted vegetables and waded with buckets of food among little squealing piglets.  By fall we were digging up carrots and potatoes and trying to avoid being bowled over by big, fat porkers.

By fall we were digging up carrots and potatoes and trying to avoid being bowled over by big, fat porkers.

In between we kept on cutting and splitting wood.

Why all the fond farm memories?

Because today I can zip off to the grocery store for food, and I can flip a switch on the wall for heat, I tend to forget the hard work that it takes to grow and harvest all I use. I bet you do, too. We also don’t experience real shortages anymore. The drought in California and the bird flu in the Midwest may have increased prices, but we can still find plenty of vegetables and eggs in the stores.

But through much of human history, and still today in many areas, people must live on what they can produce, and a bad harvest can mean a lean winter or even starvation.

The early 1800s in France was one of those times. Industrialization was changing the job market. Large factories brought people crowding into the cities. Farming was also changing. Absentee landlords were buying up land to create large, commercial farms that employed fewer people. The lack of jobs for many and low wages and poor living conditions even for many who did have work caused great social unrest. These are the years of political turmoil in France that are pictured in Les Miserables.

THE ARTIST

During these chaotic times a group of young artists broke with the art establishment and began to paint landscapes and scenes of everyday life instead of great historical events. They are known as Realists, because they painted people and places as they really looked. They are also called the Barbizon School, named for a rural village 30 miles south of Paris where many of them painted. If you remember from my blog on the Hudson River School, an artistic school means a group of artists who often know each other, sometimes paint together, and have similar artistic styles.

The Realists were among the first artists to paint in the open air (en plein air), and they inspired and helped pave the way for the Impressionists at the end of the century.

A leader of the Realists was Jean-Francois Millet, who grew up in rural Normandy. Millet showed artistic talent early, and his family sent him to study in Paris. He studied at the leading art school and with a well-known history painter.

Following the violence in Paris in the 1830s and 40s, Millet moved to Barbizon. He spent the rest of his life there, painting and raising a family of nine children. In Barbizon the subject of Millet’s art changed from portraits to scenes of rural people working at everyday tasks.

Two of his iconic and much loved paintings are The Angelus and The Sower.

THE PAINTINGS

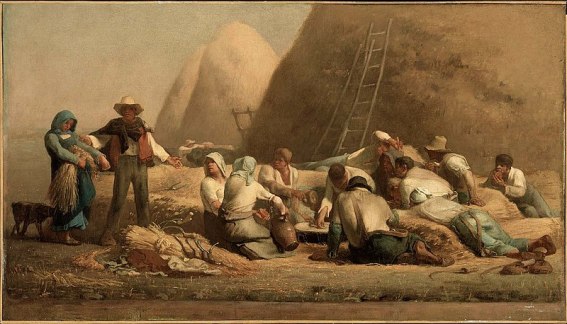

Millet painted Harvesters Resting (or Ruth and Boaz, its original title) in 1853. He returned to the subject again in 1857 with the now better-known painting, The Gleaners. The two oil paintings are each about two feet by four feet and seem to be about abundant harvests. Huge stacks of grain loom large in the first and dot the middle and background of the other.

But the actual topic is just the opposite of abundance; it is gleaning. This was a provision that allowed poor and landless people to go into already-harvested fields to pick up any grain left by the farm workers. In Leviticus 19:9-10 God told the Israelites to leave the gleanings from their fields, vineyards, and orchards, as well as the corners of their fields, for the needy.

The title, The Gleaners, is a pretty big hint about the subject, but the focal point of each painting also says, “gleaning.” Find in each of these paintings the person wearing red or reddish brown clothing. That’s the focal point, the place Millet wants you to notice first so you’ll get his message.

In Harvesters Resting Boaz is the focal point of the painting. With one arm on Ruth’s shoulder and the other gesturing toward the resting workers, his out-stretched arms create movement and bridge the gap between gleaner and worker. In The Gleaners the red hat and red sleeves of the middle woman make sure you notice these three hard-working women first.

In Millet’s time, the upper classes looked upon his paintings of peasants as ugly and threatening. In addition, Millet painted his subjects with a sculptural look that made them seem heroic, and traditionalists objected to showing peasants that way. They thought only great people from history or the Bible should be shown in that manner. In his lifetime many of his paintings were not well-received, and he never made much money.

The focal point is most important, but artists also want you to look around their paintings, and they often use color for this. Millet has used blue. It doesn’t grab our attention first thing, but it does help to unify the composition and move your eyes around. In Harvesters Resting Ruth’s clothing is the brightest area of blue. Where are the other blues? Notice how they lead you around and back to Ruth.

In The Gleaners the blue hat of the woman on the left is the brightest. Where else do you see blues that “show” you around?

In these two paintings Millet has arranged a number of people and things in groups of three. Find the groups of three grain stacks in each painting. How many groups of three stacks are in The Gleaners? Find the other figures or objects arranged in threes.

Although there are some similarities in these two paintings, there are also big differences. In Harvesters Resting everyone is in the foreground in the shadow of three huge stacks, and the workers are in various positions of rest while taking their noonday meal.

In The Gleaners it is all work; in fact, every phase of harvesting is shown in the distance. Look closely and find people cutting the grain, carrying the sheaves, stacking it on the cart, and on one of the stacks. And of course, the three gleaners are hard at work in the foreground. These three women have come to be a well-known symbol of hard work in Western art. They seem to be just a few feet in front of us.

In The Gleaners it’s easy to see the hard work of harvesting. We can almost feel the sun beating down, the scratchy stalks of wheat, and the chaff blowing into our mouths and eyes. We can imagine the ache of backs and necks that have been bent over all day.

The clues that tell you harvesting is hard work are different in Harvesters Resting. What are they?

There’s also a difference in the light. In The Gleaners the light is a little harsh and brassy, revealing the poverty of the women, but in Harvesters Resting there is a soft golden glow that makes everything seem more peaceful and secure.

One last difference: in Harvesters Resting the owner is up close and part of things. As already said, he is the focal point. But you might have trouble finding the overseer in The Gleaners. Hint: he is on a donkey. Where is he in relation to the workers?

DEVOTION

It is in these contrasts that we find our spiritual lesson. In The Gleaners there is hopelessness because there is an unbridgeable gap between the three landless and impoverished gleaners and the abundant harvest behind them.

In Harvesters Resting Boaz bridges that gap when he invites the gleaner, Ruth, to join the group that is resting and surrounded by abundance. Boaz is what the Old Testament calls a kinsman redeemer.

The dictionary defines a redeemer as someone who pays a price to ransom or save something. But in the Old Testament book of Ruth God has given us a much fuller picture of a kinsman redeemer.

In Old Testament times in Israel the land did not belong to the people, but to God, their king (Leviticus 25: 23). Each family was given the use of a portion of it, which gave them an inheritance in God’s earthly kingdom, and taught them in a down-to-earth way of their inheritance in His heavenly kingdom. So it was very important for Hebrew families to hold onto their land. If they became very poor and had to sell it, God said that a relative must redeem the land—the kinsman redeemer (Leviticus 25: 24-25).

As the story unfolds in Ruth a Hebrew family moves away from their land in Israel during a famine. While in Moab the two sons marry, but eventually both they and their father die, leaving the three women alone. Naomi and one of her daughters-in-law, Ruth, return to Israel.

In that society women without husbands or sons had little means of support and often lived in great poverty. Gleaning during harvests was often the only way to survive, and Ruth faithfully went out each day to do this back-breaking work. It was not an abundant or secure way of life. Look at how poorly the three women in The Gleaners are dressed, how hard they’re working, and how little they’re getting.

Ruth ends up gleaning in the fields of Boaz, a relative of Naomi. Bethlehem was not a huge place, and Boaz, along with most everyone, knew Naomi’s situation and that Ruth had left her homeland and her family out of her love for her mother-in-law. Boaz commends Ruth for her love and loyalty and encourages her to join his workers for mealtimes and to stay close to them for protection as she gleans. Boaz also tells his workers to leave extra for Ruth. Eventually He marries Ruth. Boaz and Ruth’s son Obed is the grandfather of King David.

Even on the surface the book of Ruth is a beautiful story of love and faithfulness. More than that, though, Ruth, and these two paintings that illustrate it, are a picture of us before and after Christ comes into our lives.

When Naomi and Ruth returned from Moab, they were in the first situation, shown in The Gleaners, poor and without hope. Before Christ we are poor and without security or hope in this life or the next.

Harvesters Resting shows Ruth after Boaz has found her and begun to put his protective arms around her.

Boaz is the kinsman redeemer, and what he does for Ruth is a beautiful picture of what Christ, our kinsman redeemer, does for us when He finds us and begins to put His arms around us.

- Read the book of Ruth and study these paintings to see and reflect on all the ways Christ, our kinsman redeemer, rescues and cares for us. Here are just a few:

He became one of us, not staying far off

He seeks us out when we are still strangers to Him

He paid the price to redeem us

He casts out our fears and provides protection for us

He gives wise counsel to us

He helps us in our work

He is pleased with and rewards our faithfulness

He provides for us abundantly

He serves us bread and wine

He uses His wisdom and power to accomplish His plan for us

He intercedes for us

He gives us His name and provides a secure home for us in this life and the next

Don’t want to miss the next Picture Lady post? Click Follow ( top right) to receive it by email.

The images in this blog are used for educational purposes only

I would like to continue to receive these. I clicked above the line and Nothing happened.

Ravyna

>

LikeLike

Click where it says Follow and it should work. You will need to put in your email.Hope you’ll try again!!

LikeLike

Fantastic teaching! Can’t wait to share it with my children…keep up the great work!

LikeLike

I’m so glad you are finding these interesting and helpful for you and your children! Thank you!

LikeLike